Urethral Cancer

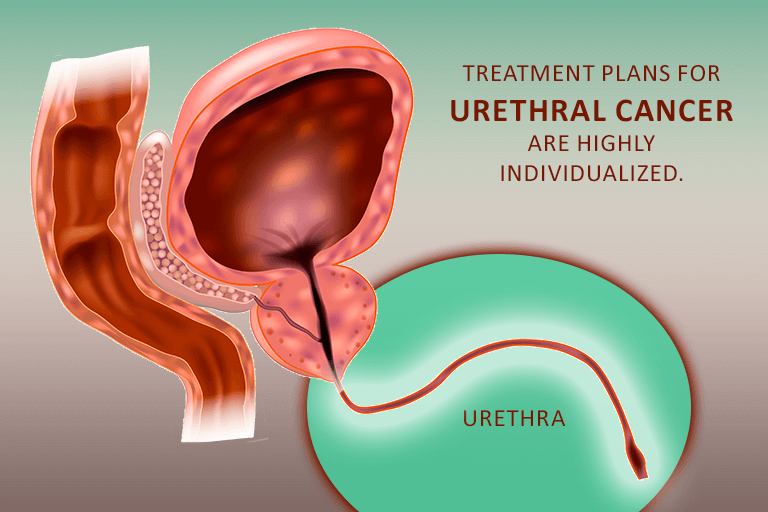

Urethral cancer affects the urethra — the tube that allows urine to flow from the bladder out of the body. Along with the bladder, ureters, and kidneys, it forms the urinary tract.

For females, the urethra is short — about 1.5 inches long. It extends from the bladder to the opening where urine flows out.

Males have much longer urethras — about 8 to 9 inches long. In this group, the urethra starts at the bladder, goes through the prostate gland, and runs the length of the penis to the opening. Men also ejaculate semen through the urethra.

Urethral cancers make up less than 1% of all cancer diagnoses and is the rarest of all urologic cancers.

Urethral cancer occurs when abnormal cells accumulate and form a tumor. Urethral cancers make up less than 1% of all cancer diagnoses and is the rarest of all urologic cancers.

Read on to learn more about urethral cancer.

Types of urethral cancer

There are 3 types of urethral cancer:

- Squamous cell carcinoma. This is the most common type. In men, it forms in the lining of the urethra in the penis. In women, it starts in the area near the bladder.

- Transitional cell carcinoma. In men, this type starts in the section of the urethra that goes through the prostate. In women, it begins near the urethral opening.

- Adenocarcinoma. In both men and women, this type of cancer forms in the glands around the urethra.

Urethral cancer is also categorized based on the part of the urethra it affects. Distal urethral cancer is found closest to the opening where urine leaves the body. Proximal urethral cancer is found in the area closest to the bladder.

Causes and risk factors

Researchers don’t know what causes urethral cancer, but they have found that it’s more common in people with certain risk factors:

- Chronic urinary tract infections (UTIs)

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

- HPV (human papillomavirus) infection, a type of STI

- A history of:

- Bladder cancer

- Urethral stricture disease (narrowing of the urethra)

- Urethral caruncle (a growth that forms on the urethra)

- Urethral diverticulum (a pouch that forms along the urethra)

- Long-term catheter use

- Smoking

- Older age (60 and over)

- African descent

Men and people assigned male at birth are also more likely to develop urethral cancer.

Symptoms of urethral cancer

People with urethral cancer don’t always have symptoms at the beginning. When symptoms do develop, they may include:

- Pain or bleeding during urination

- Poor urine flow (“stop-and-go”)

- Needing to urinate more often

- Lump on the urethra

- Clear or white discharge from the urethra

- Lump or swelling in the groin or perineum (the area between the anus and the vulva in women, and between the anus and the scrotum in men)

- Men may have a lump or thickness in the penis

Diagnosing urethral cancer

To diagnose urethral cancer, doctors usually start by taking a medical history. They ask questions about a patient’s symptoms and past health issues, such as STIs, UTIs, or other problems with the urinary tract.

There is also a physical exam. For men, this might include a digital rectal exam to check the prostate. Women might have a pelvic exam.

Other tests may include:

- Cystoscopy. The doctor uses a tool called a cystoscope to see inside the bladder and urethra.

- Ureteroscopy. This test allows the doctor to see inside the ureters — the tubes that connect the kidneys and bladder.

- Urine tests. During urinalysis, a specialist checks a urine sample for substances that might indicate urethral cancer. During urine cytology, a urine sample is checked specifically for cancer cells.

- Blood tests. A blood sample is checked for substances that may indicate cancer.

- Imaging tests. Information from a CT (“cat”) scan, MRI scan, bone scan, or chest X-ray can help doctors stage cancer by showing whether cancer cells have spread to other parts of the body.

- Biopsy. A small sample of cells from the urethra, bladder, or prostate gland are removed. A specialist then examines the samples under a microscope and checks for cancer cells.

If cancer is found, doctors will determine the grade of the tumor.

Low-grade tumors tend to grow slowly and often don’t spread. Their cells may look almost like normal urethral cells.

High-grade tumors tend to grow quickly and spread. Their cells usually look abnormal, lacking clear differentiation, structure, or discernible patterns.

Treating urethral cancer

Once a diagnosis is made, a doctor and patient will discuss treatment options. The type of treatment chosen depends on the location and extent of the cancer and the patient’s overall health. Sometimes, a combination of treatments is chosen.

Surgery

Surgery to remove the tumor is the most common treatment for urethral cancer. In some cases, the bladder, urethra, prostate, or lymph nodes are also removed.

If the tumor hasn’t spread to nearby areas, the surgeon might remove it by burning it with an electrical loop passed through a cystoscope. More invasive tumors may need more extensive surgery.

In some uncommon situations, surgery may be recommended that might involve removing all or part of the genitals. This type of surgery is considered when the cancer is found to be aggressive or has spread to the surrounding tissues and organs, making it necessary to remove it completely to try to cure the cancer or prevent it from spreading further.

The goal of this surgery, known as radical surgery, is to remove all of the cancerous cells. The urethra plays a critical role in the genitourinary system, and because of its anatomical location, sometimes the cancer can involve nearby structures. By removing the affected areas, doctors aim to ensure that the cancer does not have a chance to grow or spread.

It is a decision made with utmost care, and physicians understand the profound impact this can have on a person's identity, self-image, and sexual function. Healthcare providers are committed to providing the utmost support and resources, including counseling and reconstruction options where possible, to help patients navigate this challenging journey.

The healthcare team, which includes doctors, nurses, and specialists, will be there to offer all the medical and emotional support needed. They will explain the reasons behind such a recommendation, explore all possible alternatives, and ensure that the patient has access to the support services needed for recovery and adaptation.

When a complete removal of the penis is necessary, a surgical opening may be created in the scrotum to allow for seated urination. When only a portion of the penis is removed, efforts are made by surgeons to preserve as much tissue as possible, enabling the possibility of urinating while standing.

While the removal of genital organs can impact sexual function, many couples find alternative ways to express intimacy through affectionate gestures like kissing and touching. Furthermore, surgical techniques, such as plastic surgery, can potentially restore sexual function. For instance, a new penis can be constructed using tissue from the forearm, thigh, or back. Similarly, other body tissues, like those from the intestines or peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity), can be utilized to create a new vagina.

If the urethra or bladder is removed, a urinary diversion is created so that urine can still leave the body. There are two types of urinary diversion. The choice of diversion depends on the patient’s overall health and personal preference.

With a non-continent urinary diversion, the surgeon uses a piece of intestine to make an ileal conduit, a tube-like passageway that urine can flow through. The ureters are connected to the conduit, and urine flows out of a stoma — an opening in the abdomen. Once this system is in place, urine flows from the kidneys, through the conduit, out of the stoma, and into a urine collection bag that is worn beneath the clothes.

With a continent urinary diversion, the surgeon uses intestinal tissue to make a pouch where urine can be stored if the bladder is removed. Then a conduit and stoma are created. The person empties the pouch by placing a catheter into the stoma.

Radiation

This treatment uses X-rays and other forms of radiation to destroy cancer cells or slow their growth. Radiation is delivered in two ways:

During external radiation therapy, a special machine delivers radiation from outside the body.

Internal radiation therapy (also called brachytherapy) involves putting radioactive substances inside the body, close to the cancer cells. The substances can be delivered through needles or catheters. They might also be in tiny seeds that are surgically placed in the tissue itself.

Some patients have radiation only. Others have radiation in addition to surgery or chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy

With chemotherapy, strong drugs flow through the bloodstream to kill cancer cells. These drugs may be taken by mouth or given through an IV. Chemotherapy may be used if cancer cells have been found in other parts of the body. It can also be used along with surgery and radiation.

Active surveillance

Patients who choose active surveillance do not receive any treatment unless their situation worsens. Instead, they have routine testing to see if and how the cancer is progressing.

After treatment

After being treated for urethral cancer, patients have regular follow-up visits with their cancer care team. Doctors routinely test to make sure the cancer has not come back.

Can urethral cancer be prevented?

Urethral cancer is rare, and scientists are still studying ways it might be prevented.. But there are known ways to lower risk.

Safe sex. Use condoms and dental dams during every sexual encounter to lower risk for STIs.

Wash the urethral area regularly. Taking this step can lower risk for urinary tract infections. Women should always wipe “front to back” after urinating or having a bowel movement. Menstrual pads and tampons should be changed regularly as well.

Make a plan to stop smoking. Smoking is a risk factor for urethral cancer.

Resources

American Cancer Society

“Rare Cancers, Cancer Subtypes, and Pre-Cancers”

(Last revised: February 7, 2022)

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/rare-cancers.html

Cleveland Clinic

“Penectomy”

(Last reviewed: April 6, 2022)

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/22806-penectomy

“Phalloplasty”

(Last reviewed: June 10, 2021)

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/21585-phalloplasty

“Urethra”

(Last reviewed: May 5, 2022)

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/23002-urethra

“Urethral Cancer”

(Last reviewed: December 7, 2022)

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/6223-urethral-cancer

“Vaginectomy”

(Last reviewed: April 28, 2022)

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/22862-vaginectomy

“Vaginoplasty”

(Last reviewed: May 28, 2021)

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/21572-vaginoplasty

Mayo Clinic

“Brachytherapy”

(November 22, 2022)

https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/brachytherapy/about/pac-20385159

MD Anderson Cancer Center

“Cancer Grade vs. Cancer Stage”

(No date.)

https://www.mdanderson.org/patients-family/diagnosis-treatment/a-new-diagnosis/cancer-grade-vs--cancer-stage.html

Merck Manual – Consumer Version

“Urethral Cancer”

(Reviewed/Revised February 2022. Modified September 2022)

https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/kidney-and-urinary-tract-disorders/cancers-of-the-kidney-and-genitourinary-tract/urethral-cancer

National Cancer Institute

“Urethral Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version”

(Updated: October 7, 2022)

https://www.cancer.gov/types/urethral/patient/urethral-treatment-pdq

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

“Urinary Diversion”

(Last reviewed: June 2020)

https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/urologic-diseases/urinary-diversion

Urology Care Foundation

“Urethral Cancer”

https://www.urologyhealth.org/urology-a-z/u/urethral-cancer

“Urinary Diversion”

https://www.urologyhealth.org/urology-a-z/u/urinary-diversion

VeryWellHealth.com

Boskey, Elizabeth, PhD

“Different Types of Vaginoplasty”

(Updated: July 15, 2022)

https://www.verywellhealth.com/different-types-of-vaginoplasty-4171503