Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer. About 1 in 8 men will develop this disease during their lifetime, according to the American Cancer Society. And it’s the second most common cancer in men. (Lung cancer is the first.)

So when a man hears that he or a loved one has prostate cancer, it’s natural to have questions and concerns. What does the diagnosis really mean? What will treatment be like? What will happen to quality of life?

The following overview can answer many questions people have about prostate cancer.

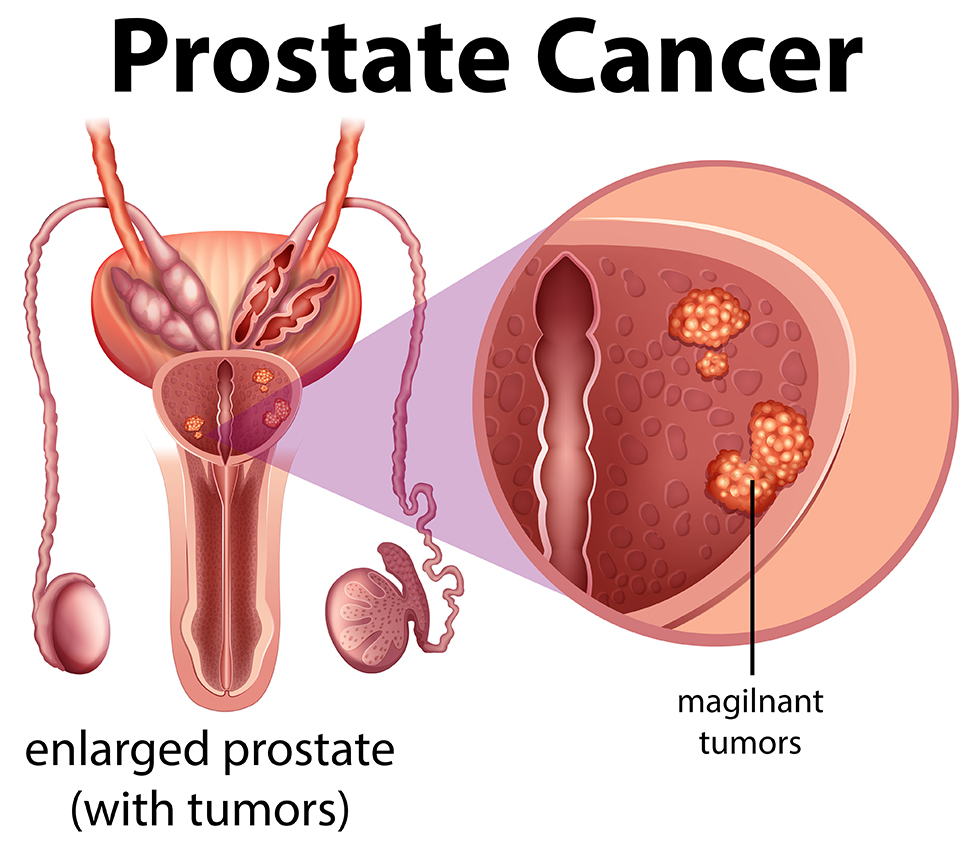

What is the prostate?

The prostate is a small gland located under the bladder and in front of the rectum. The urethra—the tube that carries urine and semen out of the body—runs through the middle.

The prostate makes prostatic fluid, a substance that mixes with sperm cells and other fluids to form semen. Prostatic fluid nourishes sperm cells and helps them move out of the urethra and toward an egg cell for fertilization.

When a man has prostate cancer, abnormal cells grow and form tumors. Sometimes, cancer cells stay within the prostate gland. But they can also spread to other parts of the body. This process is called metastasis.

Prostate cancer is typically classified by how far it has spread.

About 1 in 8 men will develop [prostate cancer] during their lifetime.

- Localized prostate cancer. Cancer cells are found only in the prostate gland itself. It has not spread beyond the prostate gland.

- Localized advanced prostate cancer. Cancer cells have spread to nearby tissues outside the prostate.

- Advanced prostate cancer. Cancer cells have spread to other parts of the body, such as the lymph nodes, bones, liver, or lungs.

What are the risk factors for prostate cancer?

Several factors contribute to a man’s risk for prostate cancer:

- Age. Men are more likely to develop prostate cancer after age 50. The average age at diagnosis is 66, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

- Family history of prostate, breast, or ovarian cancer. If a man’s brother, father, or grandfather has had prostate cancer, he is at higher risk himself. Risk also increases if he has had a relative with breast or ovarian cancer.

- Race/Ethnicity. Prostate cancer is more common in non-Hispanic Black men.

- Weight. Men over 50 who are overweight could be at higher risk.

What are the symptoms of prostate cancer?

Not all men have symptoms at the beginning. And often, symptoms are similar to those of other urological conditions, especially an enlarged prostate. Some of the more common symptoms include:

- Trouble with urination. Men might have a weak urine flow or need to urinate more often. They may also feel pain or a burning sensation when urinating.

- Erectile dysfunction.

- Blood in the urine.

- Pain or weakness. Pain may occur in the pelvis, lower back, hips, chest or bones. There might also be pain during ejaculation.

- Weight loss or poor appetite.

When should a man be screened for prostate cancer?

Through regular screening, prostate cancer is often found in an early stage, before symptoms begin.

According to guidelines from the American Urological Association (AUA), men aged 40 to 54 might consider screening if they have prostate cancer risk factors:

- African American ancestry

- A family history of prostate cancer (such as in a brother, father, or grandfather)

- Prostate cancer symptoms, such as problems with urination

The AUA suggests that men between the ages of 55 and 69, no matter what their risk, discuss screening with their doctor.

Screening is not generally recommended for men aged 70 and older or men who have a life expectancy of 10 to 15 years. However, healthy men in this age group may decide to continue with prostate cancer screenings.

Not all men have symptoms at the beginning. And often, symptoms are similar to those of other urological conditions

What tests are done to screen for prostate cancer?

Screening for prostate cancer usually starts with these tests:

PSA test

PSA stands for prostate-specific antigen, a protein made by both prostate cells and prostate cancer cells. A PSA test measures levels of PSA in the blood. If PSA tests are higher than normal (a common cutoff is 4 ng/dL), a doctor may suggest further testing.

Having a higher-than-normal PSA levels does not mean a man has cancer. Other health conditions, like an enlarged prostate or prostatitis (a prostate infection) can make PSA levels rise. So can certain medicines, recent ejaculation, and recent urologic procedures. Even aging can increase PSA levels.

Men with large prostates may have higher PSA levels also.

Digital rectal exam (DRE)

A DRE is a physical exam that allows a doctor to check the prostate directly. The doctor inserts a gloved, lubricated finger into the rectum and feels for any bumps or other abnormalities on prostate gland itself. A DRE may be a little uncomfortable, but it takes only a few moments.

If a doctor notices anything unusual on a PSA test or a DRE, they may order further testing. Sometimes, this means having another PSA test in a couple of months. It might also mean having imaging tests or a prostate biopsy.

What is a prostate biopsy?

During a prostate biopsy, small amounts of prostate tissue are removed and studied under a microscope. A biopsy is the only test that can confirm a prostate cancer diagnosis. Depending on the method used, a prostate biopsy may take anywhere from 15 to 90 minutes.

Before the biopsy begins, men are given local anesthesia. The doctor may use imaging technology, such as an ultrasound or MRI scan, to guide the process. Typically, they access the prostate in one of two ways:

- Through a small incision between the anus and scrotum

- Through the rectum

The doctor uses a needle to collect several tissue samples from the prostate. A specialist then uses a microscope to examine the samples for prostate cancer cells.

What is prostate cancer staging and grading?

If the specialist finds cancer, they will see if the cancer has spread and how fast it is growing. This is done in two ways:

- Staging. Prostate cancer is classified by stages depending on how large the original tumor is, whether cancer has spread to lymph nodes, and whether cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

- Grading. Cancer doctors use a measure called a Gleason score to grade prostate cancer. The Gleason score indicates how fast cancer cells are growing and spreading. This score helps doctors learn more about potential risk; it tells doctors whether the cancer is likely to come back after treatment.

How is prostate cancer treated?

When a man is diagnosed with prostate cancer, his doctor will help him make decisions about treatment. Prostate cancer tends to grow slowly, so in many cases, men don’t need to choose treatment right away. They can take some time to research their situation and ask questions.

When choosing a treatment plan, doctors and patients consider several factors:

- Cancer stage and grade. Some treatments work better for localized cancer. Others are more appropriate for cancer that has spread. Doctors look at how far the cancer has progressed when making treatment suggestions.

- Age and overall health. Doctors account for a man’s age, other health conditions, and life expectancy.

- Feelings about treatment. Some men want to treat their cancer immediately. Others choose to wait and see if their symptoms change or if the cancer progresses.

Treatment options can include:

- Active surveillance

- Observation/watchful waiting

- Surgery

- Radiation

- Hormone therapy

- Cryotherapy (cryoablation)

- Chemotherapy

- Immunotherapy

- Focal therapy (HIFU)

Active surveillance

Treatment doesn’t start right away. Instead, patients have regular PSA tests, digital rectal exams, imaging tests, and biopsies to keep track of how the cancer progresses. If it spreads, or if symptoms worsen, then treatment begins.

Men may choose active surveillance if their cancer is slow-growing, and they want to avoid potential treatment side effects like erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence.

Observation/watchful waiting

This approach is similar to active surveillance. However, there is less testing, and decisions about treatment are based on changes in symptoms.

Surgery

Men with localized prostate cancer may undergo a radical prostatectomy. During this procedure, a surgeon removes the whole prostate gland, the seminal vesicles (glands that make fluid found in semen), and nearby tissue. Lymph nodes may also be removed. As these tissues are removed, cancer cells are removed with them.

Today, the most common surgical approach is the robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP). A trained surgeon controls the surgery with a computer, but a robot holds and maneuvers the surgical instruments, including a tiny camera.

During a RALP, the surgeon makes several 1- to 2-inch incisions called ports in the abdomen. Ports allow the robot access to the prostate gland.

In some cases, the laparoscopic approach is used without a robot. In this instance, the surgeon holds and maneuvers the instruments.

Rarely, an open prostatectomy is done. Unlike a laparoscopic approach with small incisions, an open approach involves one 8- to 10-inch incision through which the prostate is removed.

Radiation

Radiation uses strong, radioactive rays to kill cancer cells. Radiation oncologists can deliver radiation in a few ways:

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT)

With this method, a special device delivers radiation beams from outside the body. Doctors are careful to target the cancer cells as precisely as possible to avoid risk to nearby healthy tissues.

Brachytherapy

With this type, radiation is administered from inside the body. Tiny radioactive pellets are put directly into the prostate. These pellets may be placed permanently, with the pellets giving off radiation for several weeks or months. Or the pellets may be temporary, giving off higher doses of radiation for a short time period before they are removed.

Because of radiation concerns, men who undergo brachytherapy may need to take precautions. For example, their doctor may tell them to stay away from pregnant women or children while the seeds are active.

Radiopharmaceuticals

Drugs containing radioactive substances may be used to treat prostate cancer, especially if it has spread to the bones. These injected drugs move through the bloodstream and target cancer cells.

Radiation therapy may be combined with hormone therapy, which is explained below.

Hormone therapy (androgen deprivation therapy—ADT)

The hormone testosterone fuels prostate cancer cells. Hormone therapy lowers a man’s testosterone levels so the cancer has less fuel to work with.

Hormone therapy is usually given through medications. These drugs work in different ways. Some prevent the production of luteinizing-hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH), a hormone that “tells” the body to make testosterone. Other drugs prevent testosterone from reaching the cancer cells.

Surgery to remove the testes (the glands that make testosterone) is another option, although it is rarely done in the United States.

Cryotherapy (cryoablation)

With cryotherapy, cancer cells are frozen and destroyed. Men are given anesthesia for this procedure. Using ultrasound imaging as a guide, the doctor uses a needle to deliver cold gasses, targeting the cancer cells.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy delivers medication to the entire body through an IV. It can shrink tumors and attack cancer cells that have spread to other parts of the body.

Immunotherapy

This approach uses the man’s own immune system to fight cancer cells. A special vaccine is made from the man’s white blood cells and medications. The final product is then delivered as an infusion.

Focal therapy (high-intensity focused ultrasound—HIFU)

HIFU is a relatively new treatment for prostate cancer. It uses ultrasound waves to heat and destroy cancer cells. The waves are delivered through a probe placed in the man’s rectum. They can be targeted toward cancer cells specifically, reducing the risk of harm to nearby tissues.

What are some side effects of prostate cancer treatment?

Side effects are common with prostate cancer treatments. Every man is different, and some treatments may have more side effects than others. Men and their doctors often consider side effects (and their management) when they make treatment decisions.

Erectile dysfunction (ED)

ED happens when a man cannot keep an erection firm enough for sexual activity. It’s especially common after surgery, as the nerves responsible for erections are close to the prostate gland. As much as surgeons try to avoid it, nerve damage can still occur. Radiation can also affect erectile nerves and blood vessels.

Erectile function can recover, but it takes some time. For some men, it takes just a few months. For others, it may take up to two years.

ED is treatable, however, and there are several effective therapies available. Men can try medications, self-injections, suppositories, and vacuum erection devices. In more severe cases, penile implants may be suggested. A man’s doctor can help him decide which treatments are most appropriate. (Learn more about ED and its treatment here.)

Urinary incontinence

Men may have trouble with bladder control after prostate cancer treatment. As a result, they leak urine. This problem is called incontinence. Some examples are:

- Stress urinary incontinence. A man might leak urine when he coughs, laughs, or exercises.

- Urge incontinence. The urge to urinate comes on suddenly, and men might leak urine if they cannot get to the bathroom in time.

- Mixed incontinence. Men with this type have a combination of both stress urinary incontinence and urge incontinence.

Like ED, incontinence can be treated. Sometimes, simple lifestyle changes or bladder training are all that is needed. Other options include pelvic floor exercises (such as Kegel exercises), medications, nerve stimulation procedures, urethral slings, and surgery.

Learn more about urinary incontinence here.

Other side effects

During and after prostate cancer treatment, men may also experience:

- Bowel control issues

- Fatigue

- Nausea

- Low sex drive

- Changes in ejaculation (such as no ejaculation or ejaculating smaller amounts of semen)

- Moodiness

- Depression

- Poor appetite

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Osteoporosis and increased risk of bone fractures

- Increased risk of infections

Men are encouraged to discuss side effects with their cancer care team.

Living with prostate cancer

Staying as healthy as possible during prostate cancer treatment is important for maintaining a good quality of life. Eating a healthy diet and getting regular exercise can boost energy levels and emotional wellbeing.

Men need to take care of their mental health as well. Prostate cancer and its treatment can be stressful, and many men feel anxious about the future or depressed about changes in their life. Taking time to relax and enjoy time with friends and family is key. Men may also consider counseling and support groups to help them cope with cancer and treatment side effects. Doctors can offer resources and make referrals.

Resources

American Cancer Society

“About Prostate Cancer”

(Last revised: October 8, 2021)

https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/CRC/PDF/Public/8793.00.pdf

“Immunotherapy for Prostate Cancer”

(Last revised: August 1, 2019)

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/treating/vaccine-treatment.html

“Prostate Cancer Risk Factors”

(Last revised: June 9, 2020)

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html

“Prostate Cancer Stages”

(Last revised: October 8, 2021)

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/staging.html

“Signs and Symptoms of Prostate Cancer”

(Last revised: August 1, 2019)

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/signs-symptoms.html

“Treating Prostate Cancer”

https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/CRC/PDF/Public/8796.00.pdf

American Urological Association

Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ, et al.

“Early Detection of Prostate Cancer (2018)”

(Published: 2013. Reviewed and validity confirmed: 2018)

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/prostate-cancer-early-detection-guideline

Eastham JA, Auffenberg GB, Barocas DA, et al.

“Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: AUA/ASTRO Guideline (2022)”

(Published: 2022)

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/clinically-localized-prostate-cancer-aua/astro-guideline-2022

Lowrance WT, Breau RH, Chou R et al.

“Advanced Prostate Cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline (2020)”

(Published: 2021)

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/advanced-prostate-cancer

Morgan SC, Hoffman K, Loblaw DA, et al.

“Hypofractionated Radiation Therapy for Localized Prostate Cancer: An ASTRO, ASCO, and AUA Evidence-Based Guideline (2018)”

(Published: 2018)

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/prostate-cancer-hypofractionated-radiotherapy-guideline

Pisansky TM, Thompson IM, Valicenti RK et al.

“Adjuvant and Salvage Radiotherapy after Prostatectomy: ASTRO/AUA Guideline (2019)”

(ASTRO/AUA guideline. Published: 2013. Amended in 2018 & 2019)

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/prostate-cancer-adjuvant-and-salvage-radiotherapy-guideline

Cancer.net (American Society of Clinical Oncology)

“Prostate Cancer: Statistics”

(December 2022)

https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/prostate-cancer/statistics

Cleveland Clinic

“High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU)”

(Last reviewed: August 31, 2022)

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/16541-hifu-high-intensity-focused-ultrasound

MedicalNewsToday.com

Fletcher, Jenna

“What is a prostate biopsy? The procedure, recovery, results, and more”

(January 18, 2023)

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/317601

Newman, Tim

“What is the prostate gland?”

(Updated: January 6, 2023)

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/319859

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

“High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) Can Control Prostate Cancer With Fewer Side Effects”

(June 14, 2022)

https://www.mskcc.org/news/high-intensity-focused-ultrasound-hifu-can-control-prostate-cancer-fewer-side-effects

National Cancer Institute

“Cancer Stat Facts: Prostate Cancer”

https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html

“Prostate Cancer Screening (PDQ®)–Patient Version”

(Updated: May 6, 2022)

https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-screening-pdq

Prostate Cancer Foundation

“Grading Your Cancer”

https://www.pcf.org/about-prostate-cancer/diagnosis-staging-prostate-cancer/gleason-score-isup-grade/

“Localized or Locally Advanced Prostate Cancer”

https://www.pcf.org/about-prostate-cancer/diagnosis-staging-prostate-cancer/localized-locally-advanced-prostate-cancer/

Urology Care Foundation

“Chemotherapy”

https://www.urologyhealth.org/urology-a-z/p/prostate-cancer-%E2%80%93-advanced/treatment/chemotherapy

“Prostate Cancer – Advanced”

(Updated: September 2021)

https://www.urologyhealth.org/urology-a-z/a_/advanced-prostate-cancer

“Prostate Cancer – Early-Stage”

(Updated: February 2023)

https://www.urologyhealth.org/urologic-conditions/prostate-cancer