Bladder Cancer

Bladder cancer is the 6th most common cancer in the United States, according to the Urology Care Foundation. More men than women get bladder cancer, and while it can happen at any age, it’s more common in people age 75 and older.

The most frequently diagnosed type of bladder cancer in the United States and Europe is called urothelial cell carcinoma or transitional cell carcinoma. That’s the type we’re going to talk about today.

Your bladder is like a storage tank for urine. Whenever you urinate, you empty your bladder. Then it gradually fills until it’s time to urinate again. The bladder’s flexible wall is made up of five layers. The mucosa (urothelium) is the innermost layer. Behind that is the lamina propria. Next, you’ll find the muscle. Beyond that are a layer of fatty tissue and the outside layer – the peritoneum – which surrounds and protects the whole bladder.

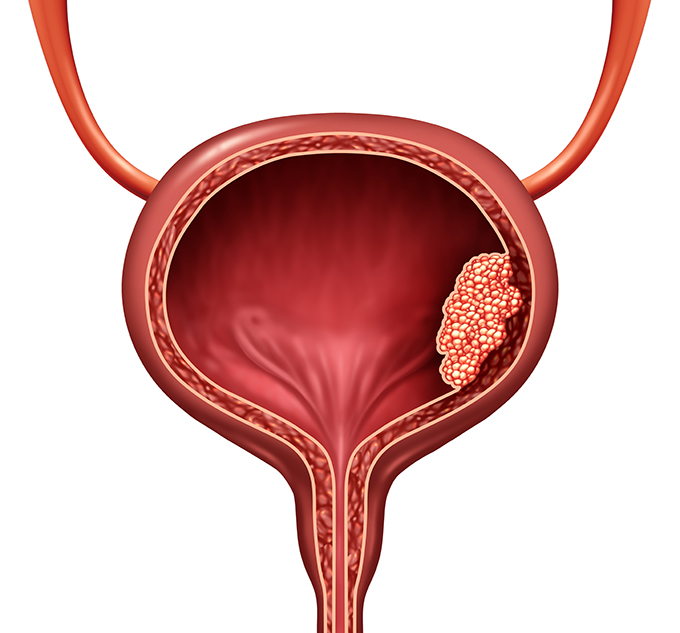

In general, bladder cancer is classified in one of two ways, depending on whether cancer cells have reached the muscle layer. The deeper cancer grows into the wall, the more advanced it is. This classification helps us choose a path for treatment.

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC)

Most cases of bladder cancer (70% - 75%) fall into this category. In this situation, cancer cells may have penetrated the bladder’s two inner layers. But they haven’t yet reached the muscle.

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer is sometimes called superficial bladder cancer because it is affecting only the “surface” inner layers of the bladder. However, this type of cancer can still progress to the deeper layers.

You might also see the terms T0 or T1 to describe this type of cancer.

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC)

With this type of bladder cancer, cells have penetrated the muscle layer and, in some cases, the fat layer beyond it. Muscle invasive bladder cancer is more serious and often requires surgical bladder removal as part of treatment. You might see the terms T2, T3, and T4 associated with this type.

Regardless of the type, bladder cancer has similar risk factors, symptoms, and diagnostic procedures.

Bladder Cancer Risk Factors

What increases your risk for bladder cancer?

- Smoking. People who smoke cigarettes are 2 to 4 times more likely to develop bladder cancer than nonsmokers. In fact, half of all bladder tumors are thought to be caused by smoking tobacco. And the more you smoke, the higher your chances of developing bladder cancer become. Even exposure to secondhand smoke raises bladder cancer risk.

- Chemical exposure. Do you work with certain chemicals to make paint, plastics, leather, rubber, or textiles? Or are levels of certain chemicals elevated where you live? Exposure to some of them, such as dyes known as “azo” compounds, could increase your bladder cancer risk.

- Some occupations seem to be at higher risk for bladder cancer, including hairdressers, machinists, printers, painters, and truck drivers.

- Genetics. Bladder cancer can run in families. If you have a relative who has had bladder cancer, you might be at higher risk yourself.

- Treatment for other cancers. If you’ve had radiation to the pelvis or taken drugs like cyclophosphamide to treat lymphoma or leukemia, you could have a higher risk for bladder cancer.

Bladder Cancer Symptoms

People with bladder cancer don’t always have symptoms. Those who do might have symptoms that mimic those of urinary tract infections, kidney stones, or other urological issues. You might have symptoms from time to time, or they might be constant. However, if you ever have any of the following symptoms, give us a call so we can do a full checkup:

- Blood in your urine. The medical term for this symptom is hematuria, and it’s the most common symptom of bladder cancer. If you have blood in your urine, it might be a pinkish or reddish color. But sometimes, the blood can’t be seen with the naked eye. This is called microscopic hematuria or microhematuria, which is found during a urinalysis, a test of your urine that’s commonly done during an annual physical.

- Changes in urination. You might leak urine, need to urinate more often, or feel a more urgent need to “go.” You might also have pain during urination (dysuria).

- Pain. You might have pain in your side, your back, or your pelvic area.

Symptoms of more advanced bladder cancer include lack of appetite, weight loss, and fatigue.

Bladder Cancer Diagnosis

To diagnose bladder cancer, we start with a complete physical exam. We’ll also ask you questions about your medical history. From there, you might have one or more of the following tests:

Urinalysis. When we analyze your urine, we check for certain types of cells, like red blood cells and white blood cells. These cells can give us clues to your urologic health.

Urine cytology. We’ll use a microscope to check your urine sample for any abnormal cells.

Blood tests. We’ll do a comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) and check your kidney and liver function.

Imaging tests. We might order a CT scan (computed tomography), MRI (magnetic resonance imaging), or kidney ultrasound to get a better picture of your, chest, pelvis, bladder, and surrounding organs.

Cystoscopy (cystourethroscopy). For screening purposes, a cystoscopy is done in our office with a flexible instrument called a cystoscope, which has a light and camera at the end. The cystoscope is placed into your bladder through your urethra. This allows us to see the inside of your bladder. We can also use the cystoscope to take a tissue sample (biopsy), which can be sent to a lab to check for cancer cells. You’ll have local anesthesia before this procedure.

We might also conduct a retrograde pyelogram, an x-ray imaging test, during your cystoscopy to get another look at your bladder, ureters, and kidneys.

Sometimes, a more rigid cystoscope is used. This type of instrument is bigger so that surgical instruments can be sent through it. If we use a rigid cystoscope, you’ll have full/general anesthesia.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT)

A TURBT procedure is similar to the cystoscopy described above, which allows us to examine your urethra and bladder. We go ahead with TURBT if previous testing suggests that you have cancer. TURBT provides us with more information about your cancer, such as tumor size, number, and location, so we can make further treatment decisions. Tumors can also be removed during TURBT.

We perform TURBT procedures at a hospital, and you’ll have general or spinal anesthesia beforehand. You’ll probably be able to go home the same day. You might have a catheter to drain urine for a day or two. We’ll show you exactly how to manage it.

Blue light cystoscopy. This test also uses a cystoscope. First, the doctor places a special imaging solution into your bladder. After an hour or so, the doctor examines your bladder with the cystoscope, but uses a blue light. The solution makes cancer cells easier to see in blue light.

Bladder Cancer Treatment

As we mentioned above, your bladder cancer treatment will largely depend on how deeply cancer cells have penetrated your bladder wall. We’ll also consider your overall health, and the type of tumor you have.

Before any treatment begins, we’ll talk with you about potential complications and the impact treatment may have on your quality of life.

Treatment of Non-Muscle-Invasive (Superficial) Bladder Cancer (NMIBC)

To treat non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, we’ll start by removing as much of the tumor as we can.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT)

You will likely have a TURBT during your screening process (see above). TURBT for treatment is similar. You’ll be given anesthesia and we’ll pass a rigid cystoscope (the larger kind that doesn’t bend) through your urethra to reach the bladder. Since we can pass surgical instruments through the cystoscope, we won’t have to make any incisions. We might also conduct a blue light cystoscopy at this time for further evaluation.

During the procedure, as much of the tumor (or tumors, if you have more than one) will be removed as possible. Areas that look suspicious for cancer can also be removed.

As with a diagnostic TURBT, you might use a catheter while your bladder heals.

A few weeks after this TURBT procedure, we might recommend another one. We do this to make sure all of the tumor is gone. If any cancerous tissue has been missed, we can remove it.

Adjuvant bladder cancer therapy

Once we’ve removed the tumor(s), you’ll likely have additional treatment called adjuvant therapy.

Why? Bladder cancer recurrence is fairly common. In fact, about half of people with bladder cancer see their cancer return within a year. Adjuvant therapy can reduce the risk of recurrence.

Intravesical Therapy

With intravesical therapy, cancer-fighting drugs are placed directly into your bladder through a catheter instead of in your bloodstream with an IV line. They stay in your bladder for an hour or two, and then they are drained out. The goal is to attack any remaining cancer cells that might have broken away from the tumor and stop them from starting new tumors in the bladder wall.

Intravesical therapy may be accomplished through immunotherapy or chemotherapy. The type and duration of treatment you receive will depend on your personal situation and whether your cancer is considered low-, intermediate-, or high-risk.

Immunotherapy for Bladder Cancer

Intravesical immunotherapy taps the power of your own immune system to fight cancer cells using a drug called Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG). Like chemotherapy drugs, BCG is directed into your bladder through a catheter.

You might need several courses of immunotherapy, and overall treatment could last about 6 weeks. We might also repeat it periodically for a few years as a maintenance treatment. Side effects include urinating more frequently, pain during urination, joint pain, and flu-like symptoms. Usually, these side effects go away within 48 hours.

Chemotherapy for Bladder Cancer

Intravesical chemotherapy (“chemo”) usually involves the use of one of the following drugs: mitomycin C or gemcitabine. These drugs affect only the bladder lining.

The first course of intravesical chemotherapy is generally done within 24 hours of TURBT. If your risk of recurrence is low, you might have intravesical chemotherapy just once. But if your risk is higher, we might repeat the process once a week for about 6 weeks. We might also repeat it again in 1 to 3 years as maintenance therapy.

Side effects of chemo include more frequent urination, painful urination, flu-like symptoms, and skin rash. Usually, these side effects are temporary. If you develop a skin rash that becomes severe, we can prescribe cortisone therapy or change the type of chemotherapy drug we use.

Treatment of Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer (MIBC)

Because cancer cells have penetrated the muscle layer, muscle-invasive bladder cancer is a more advanced stage of the disease. Your treatment will depend on how much the cancer has progressed and your overall health. But typically, treatment for this type of cancer includes chemotherapy, surgery to remove the bladder, and, in some cases, radiation therapy.

Chemotherapy for Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer

Unlike chemotherapy for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, chemotherapy drugs for MIBC are directed right into your bloodstream intravenously. Cisplatin is the most commonly used drug, although it might be combined with another drug.

Usually, you can receive chemotherapy in an outpatient setting. You might need a few cycles of chemo, and we’ll let you know what you can expect.

Chemotherapy can have side effects. You might feel fatigued and weak, and you might not feel like eating much. Nausea, diarrhea, and hair loss are common. You might also get sores on your mouth or lips, and you’ll be at higher risk for infections, bruising, and bleeding. We’ll be monitoring all these symptoms with you, and we’ll be here to help you manage them.

The time frame for chemotherapy depends on your other treatments.

- Neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy (NAC). Neoadjuvant chemo is given to shrink your tumor and eliminate any random cancer cells as much as possible before bladder surgery. Generally, surgery is scheduled within 12 weeks after you finish chemo.

- Adjuvant chemotherapy. Not everyone can have chemotherapy before their surgery. In these cases, you might have adjuvant chemotherapy, which occurs after surgery. Similar to neoadjuvant therapy, the chemo drug cisplatin is used in adjuvant chemotherapy.

Radical Cystectomy (Surgical Removal of the Bladder)

It’s common for patients with MIBC to have their bladder surgically removed, either partially or completely. If cancer has spread outside the bladder, pelvic organs and/or tissues that are involved might need to be removed as well, such as lymph nodes, part of the urethra (the tube that allows urine to exit the body). Other areas that may be involved are the prostate and seminal vesicles in men, and reproductive organs adjacent to the bladder in women.

Radical cystectomy may be performed in one of two ways:

- Open cystectomy. An incision is made in your abdomen and your bladder is removed through that opening.

- Robotic cystectomy. During a robotic procedure, smaller incisions are made, and a robot will hold the surgical instruments. The robot is controlled by the surgeon at all times. People who have robotic surgeries tend to have less pain and lose less blood.

After surgery, you’ll need to take it easy and give yourself time to heal. You might be in the hospital for about a week and then spend the rest of your recovery period at home. We’ll give you complete instructions for your recovery and prescribe medicine for pain. Most patients can go back to their day-to-day lives within 6 weeks of surgery.

Urinary Diversion

When you have your bladder removed, your surgeon will create a way for urine to leave your body. This process is called urinary diversion. Depending on your situation and preferences, this can be accomplished in a few ways:

- Ileal conduit/urostomy. With this method, the surgeon uses a piece of your bowel (intestine) to make a stoma (an opening) on your skin near your stomach. Your ureters, which typically connect the kidneys to the bladder, will be diverted to the stoma instead. Urine will drain into a special collection bag that you will wear outside your body and empty throughout the day.

- Continent cutaneous reservoir. Your surgeon will create a pouch from a piece of your intestine and attach it to a stoma in your abdomen. You’ll use a catheter to drain your urine.

- Orthotopic neobladder. In this case, your surgeon will make a neobladder – an internal pouch – and connect your ureters to it. With a neobladder, you will be able to urinate like you did before. There is no collection bag or catheter involved.

Before you leave the hospital, you’ll receive full instructions on how to manage and care for your urinary diversion method.

Partial Bladder Removal

In fewer than 5% of cases, patients have a partial cystectomy, which means that only part of the bladder is removed. This procedure may be possible for people whose tumor is in one concentrated area.

After a partial cystectomy, you should be able to urinate the same way you used to.

Bladder Preservation

There are occasionally cases of MIBC when the bladder can be spared due to the limited spread of cancer into the muscle wall.

If you’re undergoing bladder preservation, you’ll have a TURBT procedure similar to what we’ve described above (see the section on non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer). However, the surgeon will cut tumors deeper into your bladder wall. You’ll also have chemotherapy – as described above - and in addition, radiation therapy. Radiation therapy is carried out over the course of several weeks. It doesn’t hurt, but sometimes causes nausea or fatigue afterward.

Bladder preservation has a higher risk of cancer recurrence. The American Urological Association estimates that 30% of patients who follow this treatment path have a recurrence of MIBC.. We will monitor your progress with routine CT scans, cystoscopy, and urine cytology.

We work with our patients to develop a treatment plan that we feel will provide the best quality of life and the lowest risk of recurrence.

Sexual Function After Cystectomy

In both men and women, an intricate network of nerves needed for sexual function are located close to the bladder. When surgery requires disrupting the nerves, it can lead to erectile dysfunction (ED) in men and vaginal dryness in women.

A surgeon’s goal is to keep these nerves intact. However, if this is not possible – or if you have any sexual difficulties after surgery – such issues can be treated. For example, many men can take medications to restore their erections. And women may use a lubricant to make intercourse more comfortable. Don’t hesitate to ask us about nerve-sparing procedures or any sexual issues that occur after surgery.

After Treatment

No matter what type of bladder cancer treatment patients have, they need to be monitored closely with regular follow-up appointments and tests. It’s important that we monitor patients closely in order to catch a recurrence as soon as possible.

Most likely, we’ll conduct imaging, cystoscopy, lab, and urine cytology tests every 3 to 6 months for up to 4 years. If there is no cancer recurrence, then we’ll see you annually after that.

Keep in mind that we are always here if you have questions or need additional help. For example, we can guide you on making good lifestyle choices to keep you healthy. And we can put you in touch with cancer support groups and counselors, which can help you cope with the day-to-day and the emotional aspects of cancer.

Resources

American Urological Association

Chang, S.S., et al.

“Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: AUA/SUO Joint Guideline (2020)”

(Published: 2016. Amended: 2020)

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

Chang, S.S., et al.

“Treatment of Non-Metastatic Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: AUA/ASCO/ASTRO/SUO Guideline (Amended 2020)”

(Published: 2016. Amended 2020)

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-metastatic-muscle-invasive-guideline

Medical News Today

Fletcher, Jenna

“What to expect with bladder removal surgery”

(May 31, 2018)

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321994

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

“Urinary Diversion”

(Last reviewed: June 2020)

https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/urologic-diseases/urinary-diversion

UpToDate.com

Black, Peter, MD, FACS, FRCSC and Wassim Kassouf, MD, CM, FRCS

“Patient education: Bladder cancer treatment; invasive cancer (Beyond the Basics)”

(Topic last updated: May 19, 2020)

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bladder-cancer-treatment-invasive-cancer-beyond-the-basics

Kassouf, Wassim, MD, CM, FRCS and Peter Black, MD, FACS, FRCSC

“Patient education: Bladder cancer treatment; non-muscle invasive (superficial) cancer (Beyond the Basics)”

(Topic last updated: April 1, 2020)

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bladder-cancer-treatment-non-muscle-invasive-superficial-cancer-beyond-the-basics

Lotan, Yair, MD and Toni K Choueiri, MD

“Patient education: Bladder cancer diagnosis and staging (Beyond the Basics)”

(Topic last updated: April 9, 2019)

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bladder-cancer-diagnosis-and-staging-beyond-the-basics

Urology Care Foundation

“Immunotherapy and Bladder Cancer”

https://www.urologyhealth.org/resources/immunotherapy-and-bladder-cancer

“What is Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer (MIBC)?”

https://urologyhealth.org/urology-a-z/m/muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer

”What is Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer?”

(Updated: August 8, 2020)

https://urologyhealth.org/urology-a-z/n/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer